The entire criminal case against White focused on the prosecution's argument that White had committed perjury and vote fraud by registering to vote and casting a single ballot in one primary election in May, 2010 using the Fishers address of his former wife on Broad Leaf Lane instead of a new condominium he purchased in 2010 on Overview Drive. White had given up an apartment he rented following his divorce from his first wife with the plan of moving into the Overview Drive condominium once he and his second wife were married. White's then-fiancee' moved into the condominium with her children in early 2010 a few months prior to their marriage on Memorial Day weekend. White claimed he did not make the Overview Drive his permanent residence until after the couple was married. White says that he spent many nights sleeping in the finished basement of his ex-wife's house where his son lived and other places while he was busy traveling the state campaigning for the Republican nomination for secretary of state. In September, 2010, White changed his voter registration to the Overview Drive condominium in accordance with Indiana law

The prosecution argued that White committed vote fraud and perjury by claiming the Broad Leaf residence rather than the Overview Drive residence as his residence when he registered and voted using that address in the May, 2010 primary election. During the appeal of the civil case seeking White's removal as Secretary of State, the Attorney General flatly asserted in the brief it filed with the Supreme Court that White was legally registered to vote at the Broad Leaf residence and did not commit vote fraud by casting a ballot using that residence in the May, 2010 primary election. The Attorney General criticized the Marion Circuit Court's conclusions to the contrary as "fail[ing] in its obligation to abide this Court's tripartite command to liberally construe election statutes to effectuate their purpose of securing free and equal elections, uphold the will of the electorate, and prevent disenfranchisement."

In the Recount Commission case, the Attorney General contended that White's residence at Broad Leaf was a legally permissible "nontraditional residence" under Indiana's Election Code. “He was also properly registered at the Broad Leaf house," the Attorney General argued. Continuing, he explained that White "had abandoned all other residences to which he could return." "Broad Leaf was also the home of his immediate family because his son lived there." "Generally, Broad Leaf was a 'nontraditional residence,' which election law defines as not fixed or permanent. He intended to live there until he was married and moved to the Overview Drive Condominium." The Attorney General observed that the question of where White was registered to vote and when he voted using that address are "both technical and formal." To find that White's voter registration and ballot casting using the Broad Leaf residence amounted to fraud was a "an absurd and arguably unconstitutional result" that "the legislature could not have intended."

The Indiana Code defines a person’s residence as “where the person has the person’s true, fixed, and permanent home and principal residence; and to which the person has , whenever absent, the intention of returning.” Additionally, the code provides standards to assist in the determination of the person’s residency. A person’s residence may be established by their origin or birth, intent and conduct to implement the intent, or operation of law. A person does not have residence in more than one precinct. Once a person obtains residency in a precinct, they retain residency there until they abandon the residency by 1) having the intent to abandon the residence, 2) having the intent to abandon the residency, and 3) effectuates that intent by actually establishing a residence in a new precinct. These provisions codify much of this Court’s discussion of residency and domicile in State Election Board v. Bayh . . .

Other statutory provisions create rebuttable presumptions assisting in determining a person’s residence. . . White had abandoned all other residences to which he could return or intend to return. . .For example, the place where a person’s immediate family resides is the person’s residence. White’s only immediate family was his son, who lived at the Broad Leaf house. The Commission properly found that this qualified White to declare the Broad Leaf house on his voter registration . . .

The Election Code provides for a person to have a “nontraditional residence” which may be the best description of White’s living arrangements . . . an individual with a nontraditional residence whose residence is within a precinct, but is not fixed or permanent, resides in that precinct . . .White intended that Broad Leaf house to be his principal residence from the time he abandoned the Pintail Lane apartment and until he was married and moved into the Overview Drive condominium with his then-fiancee. He had his mail forwarded to the Broad Leaf house, lived in the finished basement, had 24-hour access to the house through a key and a security code. He changed his driver’s license to reflect the Broad Leaf address. Whether a traditional or nontraditional residence, the Commission’s factual determination that the Broad Leaf house was White’s residence from June 1, 2009 to June 1, 2010, is not arbitrary or capricious and the trial court erred in reversing. The Commission’s determination finds support in this Court’s jurisprudence as well. (citations omitted)At trial, the jury was instructed to rely solely on White's "true, fixed, and permanent home and principal residence; and to which the person has , whenever absent, the intention of returning” as the definition of residence for both his voter registration and ballot casting. In his reply brief in White's appeal of his criminal convictions, the Attorney General concedes the existence of statutory and case law defining the varying legal standards that are to be applied in determining a person's residence as argued by White. Nonetheless, he argued that the narrow instruction the trial court provided to the jury in White's case was "accurate, broadly applicable, and could be understood by the jurors." A more detailed instruction that would have allowed the jurors to consider the varying standards would have only "confused" the jurors he argues, and it was an objection White's attorney, Carl Brizzi, had failed to preserve for appeal the Attorney General argues. The convictions based on the jury instruction on the narrow definition of residence can only be overturned if the appellate court finds that the trial court committed fundamental error because of Brizzi's failure to preserve his objection to the jury instruction.

Similarly, the Attorney General is dismissive of White's claims that jurors were incorrectly instructed on the application of the vote fraud statutes, which make it a crime to fraudulently complete voter registration applications or cast ballots fraudulently. Jurors were instructed that the applicable statutes applied to a single voter registration application or a single ballot despite the fact the statute was written in the plural to apply to "applications" or "ballots." The Attorney General's brief in the Recount Commission case emphasized the fact there was no question that White was entitled to register to vote in Hamilton County and was in fact a registered voter at all applicable times in that country. Yet the Attorney General claims it would be absurd to think the legislature only meant to prosecute people for vote fraud if they completed more than one voter registration application or cast more than one ballot.

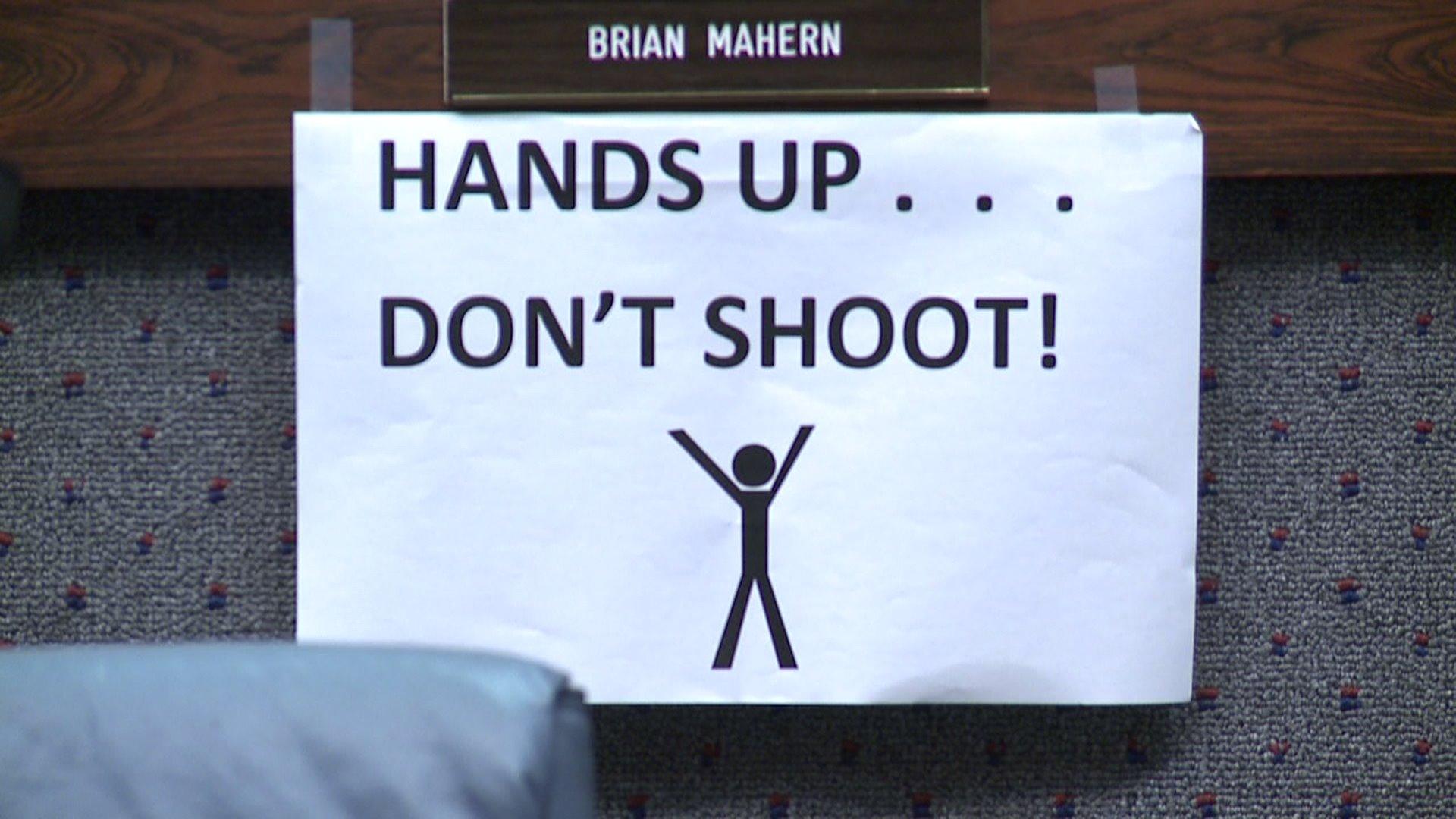

The overriding purpose of the voter registration laws is to ensure the constitutional principle of one man, one vote. How can you convict White of two felony counts of vote fraud and two felony counts of perjury for registering in a precinct in the same town within the same county and casting a single ballot in one election when the Attorney General concedes he was a legally registered voter of that town and county entitled to cast a vote on the basis that he should have registered and voted in a different precinct than he was registered and voted? Does that not fly in the face of the Attorney General's previous argument that our election laws are to be "liberally construed" to "prevent disenfranchisement"? Is that the form of vote fraud the legislature intended that persons could be prosecuted for when they enacted those laws? I think not. Lest we forget that the Marion Co. Election Board determined that former Sen. Richard Lugar had illegally registered and cast ballots repeatedly from an address at which he had no legal claim for arguing was his legal residence for 35 years. Was he prosecuted? Absolutely not. In fact, this same Attorney General actually defended Lugar's clearly illegal voter registration as legal.

Other arguments proffered by the Attorney General in his brief are equally as concerning. White was found guilty of felony perjury for listing the Broad Leaf address instead of the Overview Drive address on the marriage license application he completed for the Hamilton Co. Clerk's Office. The Attorney General agrees that White was a resident of Hamilton Co. when he completed the marriage license application but that he made a material misrepresentation on the application by listing the Broad Leaf address as his residence. The Attorney General cites no cases in support of its argument that a person's address on a marriage license application can be the basis for finding a person guilty of perjury but chides White for not providing any cited cases for the proposition that his county of residence was the material information requested, not a more exacting, "true, fixed and permanent" address at which he resided. I venture to guess that many unmarried persons shacking up prior to their marriage use different addresses on their marriage license application, none of whom are ever prosecuted for having done so.

The marriage application also asks for your place of birth. Undocumented aliens are allowed to marry in Indiana despite their illegal status; however, it would not surprise me if some of them misrepresent their place of birth, which the license also requests, due to the misapprehension that their license application will be turned down if they were born outside the country and aren't either a lawful permanent resident or legally visiting the country. The primary purpose of the marriage license application is to establish that applicants are who they represent themselves to be, and that they are legally eligible to marry. Logic would dictate to me that the use of aliases, misrepresentations of dates of birth and one's marital status are the only material misrepresentations that lawmakers contemplated could serve as the basis for a criminal charge arising out of the completion of a marriage license application.

Another felony conviction White is appealing is a theft conviction regarding the fact that he drew a paycheck as a Fishers town council member during a several month period after he had moved out of the district from which he was elected to serve before he resigned from the council. White was elected at-large by all residents of Fishers, although he represented a geographically-defined district. Although White returned the salary he earned during the months he continued to draw after he moved out of his district, the attorney for the Fisher's town council argued that he was under no obligation to return it. White had continued attending meetings and otherwise fulfilling his statutory duties. The town council never exercised its authority under state law to remove him from office, and nobody initiated a quo warranto action seeking a judicial determination that he was not eligible to hold the office to which he had been elected and duly sworn in. White relies on case law that holds that a person holding office under color of law is a de facto elected official entitled to exercise his duties and receive compensation for his services even if later determined to be ineligible to hold office. The acts of a de facto elected official cannot be voided on the basis that a person was later determined to be ineligible to hold office.

This exact scenario has played out on multiple occasions in Indiana and elsewhere. No elected official has ever been charged and convicted of theft in Indiana on this basis prior to White's conviction. The Attorney General is correct in citing a state statute providing that a person is deemed to have vacated his office as a town council member when he ceases to be a resident of the district from which he was elected to serve. The Attorney General argues that White's office was vacant the day he moved out of the district because he forfeited the office under operation of law, and that he committed theft by continuing to draw his salary from that day forward. The Attorney General argues that a resolution of the town council declaring White's seat vacant or quo warranto action are merely alternative and not exclusive remedies that could have been undertaken to remove White from office.

Was Patrice Abduallah prosecuted for theft after he drew his $15,000 a year salary as an Indianapolis City-County Councilor for more than three and a half years before he resigned his office after this blog reported that he didn't reside in his district? Was he prosecuted for completing a voter application and casting a ballot from a home in which he did not reside? No on both counts. A city council member in Mitchell, who didn't even live within the municipal boundaries of the city let alone the district to which he was elected, successfully sued and won back the salary that had been withheld from him on the theory that he was a de facto council member until legally removed from office. I don't recall the Attorney General stepping in to argue otherwise in that case. Taking the Attorney General's argument at face value, Brownsburg town council member Rob Kendall, who has been accused of violating the state constitution's prohibition against holding more than one lucrative office at the same time, could be charged with theft because he continued drawing his town council salary after he accepted appointment to another lucrative office. That's because he would have been deemed to have vacated his town council seat the moment he became ineligible to serve as town council member after he began holding a subsequent lucrative office. It seems to me a civil, not a criminal remedy, has always been the rule in Indiana until White's case.

White's appeal raises a number of other issues that I've not discussed, including ineffective counsel by his attorney, Carl Brizzi, at trial, and prosecutorial misconduct. Despite acknowledging that Brizzi made prejudicial statements suggesting White's guilt during voir dire, failed to raise numerous objections and preserve issues for appeal, mistakenly failed to enter stipulated documents into the record because he was unaware stipulated evidence still had to be formally proffered at trial, and failed to offer any defense, including exculpatory evidence, the Attorney General argues that White was not the victim of ineffective counsel. In the Recount Commission case, the Attorney General argued there was substantial evidence to support the Commission's conclusion that White resided at Broad Leaf, even if as a "nontraditional residence." In the criminal case, the Attorney General argues that there wasn't sufficient evidence in the record for a jury to conclude White had intended to reside at Broad Leaf instead of Overview. Could that be due to the fact that his attorney neglected to offer the evidence that allowed the Commission to reach a different conclusion?

It is beyond me why the powers that be in this state cannot see beyond their hatred of Charlie White to see the long-term legal ramifications of allowing White's convictions to stand. The ACLU of Indiana gets all worked up about a law requiring voters to furnish a photo identification when they appear in person to vote on election day but is silent when those same voter registration laws are strictly applied to criminally prosecute a person who nobody questions was legally eligible to register and cast a vote in the town where he was residing in Indiana. The ACLU of Indiana gets all worked up about a state law that prevents same-sex couples from being allowed to be issued a marriage license legally recognizing their marriage in Indiana but is silent when someone legally entitled to marry in this state is prosecuted for a felony simply because the person listed one address in the same town instead of another address on his marriage application when nobody argues with the fact that the person had resided at both residences within that same county at different times. If White were black, gay, Jewish or Muslim instead of being a white male Christian, do you think the ACLU would have remained silent. I think not. Civil libertarians and fair-minded persons in the rest of Indiana's legal community should be ashamed of themselves for the absence they've taken from the outrageous and politically-driven prosecution of Charlie White.